Traditional Laotian Homes Get a Second Life

Plans for some land beside the Mekong River changed when Steven Schipani of Bay Shore, New York, and his fiancée, Veomanee, decided to get married.

For some time Ms. Veomanee, who, like many in Laos, just uses one name, had intended to use the land for a hotel and spa. But in 2006, with their wedding on the horizon, the couple decided to build a house on the 1.2 acres in the village of Xang Khong in northern Laos.

“We were saying, ‘Of course, it’s a great piece of land for a commercial development, but also it’d be nice to have a residence here,”’Mr. Schipani recalled.

They both felt that their home should have modern comforts but also reflect local architectural styles. Ms. Veomanee directs Ock Pop Tok, a boutique textile gallery and weaving center in nearby Luang Prabang, which is her hometown and, as a Unesco World Heritage site, one of Laos’s main tourist attractions. Her husband is an international development specialist with a deep interest in traditional Lao culture.

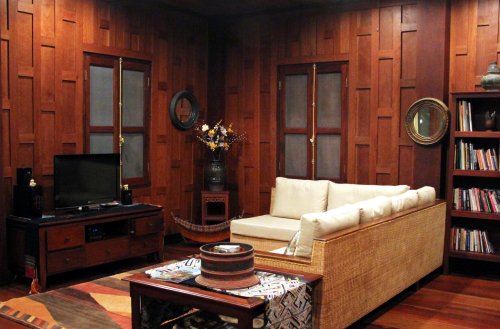

The couple looked around for traditional building materials, and discovered that three families in two nearby villages were planning to discard old homes made from rosewood and other tropical hardwoods. Mr. Schipani said the vintage wood was less likely to warp, had more character than new wood, and he saw environmental value in reusing it.

They paid about 95 million Lao kip, or about $10,000 at the time, for the wood and delivery fees. Ms. Veomanee then sketched a design for a two-level, timber-frame home with terra cotta roof tiles.

The rosewood walls of one of the salvaged houses were in such good condition, despite being about 90 years old, that the couple decided to use the entire two-level structure as one wing of the new house. The other wing would be new construction, although salvaged woods were used along with concrete.

Ms. Veomanee’s sketch included open-air breezeways on the first and second levels to separate the old and new wings.

An architect in Luang Prabang converted the sketch into a computer rendering to guide construction, and the couple hired two crews of contractors with different specializations. A Vietnamese crew built the timber-frame foundation and did woodwork in the modern wing, Mr. Schipani said, while the Lao crew framed the roof.

Decorations on the roof eaves and the door frames were completed by monks from a Luang Prabang temple. Previously they had restored Buddhist temples in the area as part of a Unesco project to conserve artisanal woodworking techniques, Mr. Schipani added.

The entire project, which began in 2007, cost about 1.2 billion kips, or $150,000, and took about a year and a half to complete, said Mr. Schipani, who first came to Southeast Asia in the 1990s as a Peace Corps volunteer in northeastern Thailand and has lived in the region for two decades.

“The way it came out,” he said, “was very similar to what I was thinking” in the planning stages. But, he added, construction proceeded slowly at times, partly because the contractors’ handiwork did not always live up to the couple’s standards. For example, the first versions of some windows were not always level and some doors did not close properly.

The couple also went to great lengths to acquire some building materials. The bathroom tiles, for example, were purchased in Bangkok and carried home in their suitcases on the 90-minute flight. (When they realized they were short by a few tiles, Mr. Schipani made a special trip for another box.)

In a few cases, fittings or other materials that they had ordered from Thailand or China turned out not to be suitable. In some cases, they decided to modify their designs to use whatever was available locally. “A little bit like the tail wagging the dog,” Mr. Schipani said with a laugh as he sat on the backyard patio one recent afternoon.

Completed in late 2008, the 350-square-meter, or 3,767-square-foot, home was painted in a light-yellow hue that glows at sunset.

The couple said the open-plan layouts of the kitchen and upstairs living room were ideal for entertaining family and friends during Lao New Year, in mid-April, and other festive occasions.

The interior decoration also reflects their interests in traditional Lao culture. For example, there are handwoven hangings in several rooms, and while one room in the vintage wing displays traditional gongs and shields from some of the country’s ethnic minorities, another is a prayer room with a Buddhist altar.

Mr. Schipani said he landscaped the property, which slopes gracefully down toward the Mekong. The backyard includes his collection of native orchids, some century-old sandalwood and tamarind trees, and a range of fruit trees.

As they talked about the house, Mr. Schipani and Ms. Veomanee were on the patio, eating fresh papayas and watching their 4-year-old son, Alvee, run along the breezeway.

Mr. Schipani, who now works in Bangkok during the week, said he loved coming back to Xang Khong on weekends and vacations. The house is a 10-minute boat ride from Luang Prabang’s historic downtown and less than three miles from the international airport.

The house is just a short walk from the homes of Ms. Veomanee’s parents and two of her brothers. As a result, Alvee has a lot of friendly cousins to play with, something that reminds Mr. Schipani of his own childhood on Long Island.

The family spends summers in Bay Shore, where Mr. Schipani still owns a home. But while they enjoy visiting the United States, they have no plans to move there. Ms. Veomanee said she loved living near her parents and siblings, and her husband said he eventually might pursue a sustainable agriculture project on some wooded land across the Mekong.

“You have the best of both worlds,” Mr. Schipani said about living near Luang Prabang. “We have good restaurants and interesting things to do, and the natural environment is stunning. And then, if we want to hop on a plane and be in a big city, we can.”

Source: The New York Times