Finally, A Licensed Dengue Vaccine

Source: The Straits Times

Despite its 60% efficacy, it may cut dengue burden substantially in many countries

Vaccines for infectious diseases are among the health achievements that have had a major public health impact.

Smallpox was eradicated because of vaccination. It was recently estimated that since 1924, vaccinations have prevented 103 million cases of childhood infection, representing approximately 95 per cent of infections that would have occurred, including 26 million in the last decade alone.

Although all vaccines may result in a substantial reduction in disease, some do not offer complete protection against infection. Many vaccines do not offer above 90 per cent efficacy. Some novel ones such as malaria and rotavirus vaccines, and even some of the established vaccines (influenza and pneumococcal) offer only “partial efficacy”. They are able to reduce disease incidence by 60 per cent or less.

While good efficacy is important, the ultimate goal of vaccination goes far beyond that. Thus, there is a need to provide a broader perspective in evaluating vaccines.

This should include not only how much disease and death can be averted, but also how many hospitalisations can be reduced to minimise the pressure on health systems, and how much indirect protection a vaccine can achieve by reducing virus transmission.

A vaccine, even if it has only moderate efficacy, could have a major public health impact if the particular disease has a high incidence.

Dengue is such a disease, with a very high burden in many endemic countries.

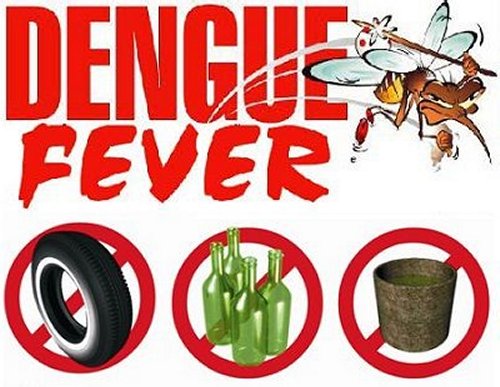

Dengue infections can have a severe and sudden onset, with bleeding tendencies and shock. Dengue is primarily an urban disease and large explosive epidemics with thousands of cases are common. Patients often require hospitalisation, overwhelming healthcare systems during these epidemics.

In a recent study published by Nanyang Technological University on the rise of dengue in Singapore over the past three decades, findings showed that as the local population grew and, with increasing urban density, the chances of a person getting infected also rose.

There is a desperate need to prevent and control the disease, especially in its epidemic form. A dengue vaccine provides one of the most effective ways to do this.

Decades of attempts to develop a dengue vaccine have shown how challenging it is to come up with a highly efficacious one.

But now we have reached a major milestone in the history of dengue control: the first dengue vaccine was recently given the green light by Mexico, the Philippines and Brazil, with many other countries poised to follow.

Developed by Sanofi Pasteur, this vaccine has been tested in over 30,000 children aged two to 16 years in 10 highly endemic countries in Asia and Latin America. The data from these trials showed an overall efficacy against dengue of any severity and against any of the four serotypes of 60 per cent.

Efficacy differed by serotype, prior dengue exposure and age. Among individuals aged nine years and older, efficacy was higher than in younger children. Efficacy against severe dengue and hospitalisation was substantial (93 per cent and 81 per cent, respectively) in those aged nine years or older, compared with 45 per cent and 56 per cent in children younger than nine years.

It also appeared to be safer in individuals aged nine and older. In this group, not only was efficacy higher, but it was also safe throughout the three years’ observation time that we have to date. The vaccine will hence be licensed only for those aged nine to 45 years.

So after 70 years of trial and error, we finally have the first dengue vaccine.

It is not perfect.

But while the scientific community continues to work on how to develop an even better vaccine, countriesfacing major dengue outbreaks need to decide how best to use the first dengue vaccine in history.

Despite moderate efficacy, it may still have a substantial impact on reducing the burden of dengue in many countries by reducing severe disease, mortality rates, hospitalisation and the potential for large explosive epidemics.

Integration of the vaccine with other strategies, including improved clinical case management and effective approaches to vector control, should ensure a more substantial public health impact in the long run.

Lessons learnt from an integrated dengue vaccine introduction will also pave the way for other novel vaccines that offer only partial efficacy.