From Bombs to Bracelets, This Jewelry Line Is Clearing Land Mines

“After the war, we live afraid of unexploded bombs, and we’re very careful when we go and do anything,” says Somechit Phouangsavat, an artisan from Ban Naphia, also known as War Spoon Village, in Laos.

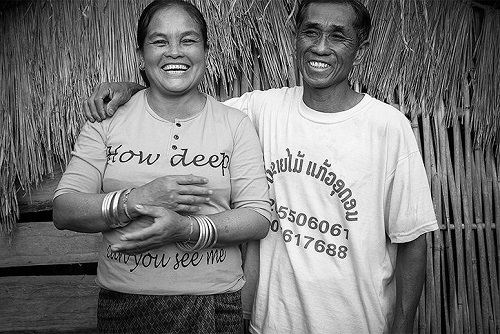

The 32-year-old works alongside 30 other artisans at Article 22, a company that makes jewelry using Vietnam War–era bombs and scrap.

“Wars don’t end when history books say they do,” explains Elizabeth Suda, the founder of Article 22. “They don’t end with a date. This war has a legacy that is alive and present.”

During the Vietnam War, the United States dropped about 2 million tons of ordnance during 580,000 bombing missions on Laos, a secret casualty. More than 40 years later, the war isn’t over in the Southeast Asian country: 80 million of the bombs dropped didn’t detonate. To this day, unexploded ordnance with the capacity to kill and maim is spread across the farmlands, gardens, and footpaths of Laos.

At the current rate of removal, it will take an estimated 800 years to clear them all.

The details of how Phouangsavat’s hometown became known as War Spoon Village are hazy. In 1975, a lone traveler journeyed through the Plain of Jars in northeastern Laos, where thousands of enormous, hollowed-out stones shaped like jars dot the earth—the Stonehenge of Southeast Asia. Legend has it the jars are the whiskey glasses of giants; today the area is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The traveler settled in the village and taught one of his neighbors how to turn bomb scrap metal into aluminum spoons. Traditionally subsistence farmers, the spoon makers started selling them for a small profit.

In another part of the world, about 30 years later, Suda graduated from Williams College and started working at Coach. As an assistant, her duties put her in close contact with the products, and she watched them move along the supply chain. “I would get the samples in and look at the tags, and I would see Mandarin scrawled in the margins,” she recalls. “It really got me thinking about what we buy and how it’s made.”

Upscale clientele are willing to invest in fashion and accessories. Suda theorized that the market existed, and if companies paid a bit more for the products they sold to bring people a livelihood or to preserve a culture, consumers would be willing to pay more. “The consumer market is a power force,” she says.

She self-funded a trip to Laos in 2008 to research ethical and sustainable textiles with Helvetas, a Swiss NGO. In War Spoon Village, she was moved and impressed to see the artisans at work after their day of farming, melting down the aluminum to make spoons. Back in the States she became “obsessed,” she says, and worked on designing a prototype bracelet that might satisfy a fashionable consumer.

A year later, the Peacebomb bangle in hand, she returned to Laos, where the spoon makers were willing to try to make something new. “I told the artisans, I can’t promise anything except I will buy the first 500,” Suda says. “And I’ll do my best to sell them, tell the story, and keep coming back for more.”

Today there are more than 40 styles based on the original gunmetal bangle bracelet, the words “Dropped + Made in Laos” on the interior. Suda says her company buys tens of thousands of the pieces across all styles, including the original.

Artisans are paid a minimum of four times more than the local price of a spoon for a product that takes the equivalent amount of time. “I make more money making the jewelry,” Phouangsavat says.

For other products that take longer to make, the artisans are paid more than 100 times the price of a spoon, and for even more time-consuming products, they are paid up to 200 times more. “Essentially, we want to pay more to reward ingenuity as well as general motivation year over year,” says Suda. She also notes that the jewelry makers are able to work from home, part-time, and per order. Artisans who don’t want to make more complex pieces can opt out. The original Peacebomb bangle retails for $50; the necklace made from shards of bombs runs at $425.

“One of the things that is gorgeous about this whole story is they are part of the change process within their own community,” Suda says, “not just in terms of recycling what you could consider as litter but in terms of the fact that their pieces are sold, and each piece then helps to clear unexploded bombs from their land.”

The proceeds from each purchase, depending on price, help rid the land of mines, from one square meter up to 30 square meters. The flagship Peacebomb bangle, for example, demines three meters of land. The Full Circle Set necklace clears 16 square meters of bomb-littered land so Laotians can work safely in their fields. The land that is cleared is the very ground on which the artisans live and work.

In 2014, one of the artisans had Mines Advisory Group demine 400 pieces of unexploded ordnance from his three-hectare rice field. His family had been farming the land for 40 years knowing it was contaminated but knowing they had to use it so they could eat.

War Spoon Village is home to approximately 300 people, but only 30 are official Article 22 artisans. “We thought it would be nice if our presence there could benefit more than just the immediate artisan families,” says Suda. To better impact the community, 10 percent of the proceeds from the jewelry Article 22 buys goes toward the village development fund, which is administered by the chiefs in conjunction with the NGO Helvetas.

The village is about two hours from the provincial capital. Suda says when she started traveling there it wasn’t on the traditional grid, as it is now. The roads aren’t yet paved, but they are cleared, making transport smoother.

Thinking about the United States’ legacy in Laos, Phouangsavat says, “We feel sad heart with [what] the strong country did with the weakest country, because we [had] no way to fight them. Why [did] they do this to the people no way to fight?”

The “Secret War” in Laos isn’t taught in most high schools, and a lot of Americans don’t know about the devastation their nation brought on Vietnam’s neighbor. So Suda sees the Article 22 jewelry as a vehicle for storytelling and information sharing. “People that wear the jewelry, in a way, are storytellers. It’s a conversation piece,” she says.

Source: Yahoo News