Lao And Now: Mekong River, Vientiane, Thailand

Source: The Australian

“We think kids are old enough to go to school when they can reach over their head and touch their opposite ear,” says the young Lao schoolteacher at the village of Ban Phar Leib on a remote stretch of the Mekong River.

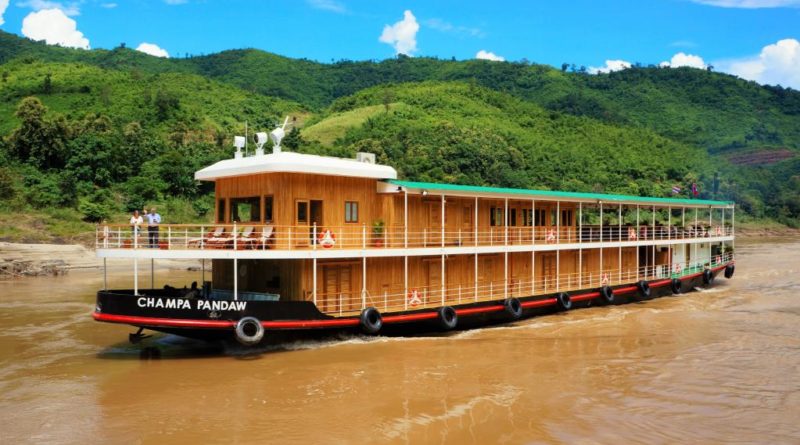

Among tribal communities, where record-keeping can be a low priority, the “touch-your-ear” age gauge seems to work well enough. A gaggle of healthy Lao kids lines up in front of their two-room school to lustily sing us their national anthem. After distributing pens and notebooks (but no sweets) we are taken in hand by the grinning youngsters and escorted from the premises, so to speak, through the village to our ship, Champa Pandaw.

We’re cruising up the Mekong from Vientiane, capital of Laos, to northern Thailand, on a 1000km, 10-day journey. Way upstream, dams are voraciously draining the river, so initially we have had to drive north for several hours, the water level at Vientiane being too low for even our vessel’s 1.6m draft.

Champa Pandaw is a flash reincarnation of the classic Irrawaddy Flotilla steamer, all teak and brass, plus air-conditioning, ensuites and G&Ts. We turn upstream and slip into Lao time. (For the Lao people, the name of their country is not the francophone invention, Laos — rhyming in English with either “chaos” or “house” — but simply Lao, rhyming with “now”.)

The Mekong, Asia’s “Big Muddy”, tumbles from heaven to earth, from Tibet to the South China Sea, coursing 4300km through six countries. The mid-section of its journey, the 700km passage through landlocked Laos, sees whirlpools and reefs give way to tranquil, sunny reaches, then narrow gorges and mazes of sandbanks.

We go ashore often, our first visit being to the former French administrative town of Pak Lai where yellowing colonial buildings stand alongside a Buddhist wat.

A monk rings the temple’s long, curiously shaped bell, the casing of an old American artillery shell. A red and yellow hammer-and-sickle flag is a reminder of the system of government here. The Lao Peoples Democratic Republic (the country’s official name) embodies a wondrous, multi-layered oxymoron — one-party democratic communist capitalism.

We cruise through gorges where the teak and bamboo-forested walls would still look familiar to its original Iron Age settlers, but in fact we are already in the Hydro Age. Rounding a bend, our way is blocked by the huge, new Sayaburi hydro-electric dam.

Laos, resource-poor except for its Mekong waters, has two dams under construction and seven more proposed. Nicknamed “the battery of Southeast Asia”, it will sell 95 per cent of the Sayaburi power to neighbouring Thailand. We slip into a lock on the western flank of the dam. Gates close behind us, water rushes in and our 200- tonne ship effortlessly climbs a water stair, as it were.

The Mekong, the world’s 10th-longest river, is a liquid highway, the eternal “route one” of Southeast Asian trade and migration. Country boats, with curved hulls like warped pencil cases, chug from Vientiane up to Luang Prabang and beyond while yowling “long tail” speedboats — think of a waterski with a hot-rod engine and seats — tear from village to village. Slender pirogues are in the mix, as well as cargo craft plodding against the five knot current as far up as Jinghong, China.

Our captain, 62-year-old Xieng Souk, reads the river’s whorls like a palmist might view a hand. No electronics for him, just eyes that for 40 years have studied every braided channel, bar and dragon-toothed shoal. We travel only by daylight and moor at night beside jungle beaches.

The 23 passengers on my voyage consist of roughly equal numbers of British, Americans, Australians, Swiss and French. With no fixed seating at meals, we move and mix freely. I hear fascinating life-tales of French-era Vietnam, lobster fishing in Maine, submarine service and much more. Two American couples, travelling separately, must discreetly assess on which side of today’s “Trump line” their compatriots fall. Sensing affinity, they can then go with the Mekong flow.

Hiking ashore each day in the villages of animist Hmong and Khmu people, or Buddhist Lao communities, we get almost enough exercise to work off our Cambodian chefs’ excellent three-course feasts.

On land we visit schools (some, sadly, with no teacher), small wats, markets and local weavers. It’s a water margin world of wood smoke, bamboo and thatch, plus satellite dishes, outboards and mobile phones.

We roll ever northwards past gold panners, slash-and-burn croppers, reed gatherers and boat builders. Luminous forests might still shelter gibbons, langurs and perhaps even clouded leopards, but such creatures now keep sensibly beyond the range of hunters’ rifles and thus tourist lenses.

On surprisingly cold mornings we wake to find dense mists cloaking the river. The sun soon burns through the monochrome dawn and the landscape takes on colour like a photographic print developing. The shore, too, morphs from low dunes to jungle walls and fertile flats.

Then, 300km north of Vientiane, we hit the mecca of Luang Prabang.

With its 32 temples, this mother-lode of Buddhism, French heritage and royal Lao history is one of the best-preserved colonial towns in Asia. At dawn monks drift through its UNESCO-listed streets, accepting food donations from would-be merit-makers. (Does a photographer score demerits by giving them 1/30th second at ISO 400 rather than more noodles and sugar drinks?)

A few hours later in trendy cafes along those same historic streets, Western hipster baristas hawk lattes at Western prices to flash-packers.

Luang Prabang’s golden-roofed wats glitter against the river’s slow-boat tide. We linger for two nights, with plenty to do. I love the 1904 Royal Palace, now the National Museum. Where else can you see under one roof a 1959 Ford Edsel (post-regal, clapped-out), a Queensland boomerang (Australian government gift) and a moon rock (official Richard Nixon gift before he bombed the neutral kingdom), plus a photo of laughing Ho Chi Minh dancing with Sisavang Vatthana, the last Lao king, and two girls?

Other than the gilded, 400-year-old Wat Xieng Thong temple, the best spiritual trip in town is to find a riverbank cafe from which to contemplate a Mekong sunset over a chilled Beer Lao and fresh-grilled satays. The most anomalous trip is to look across the road and see a World Heritage-listed massage parlour.

Continuing north, we visit the mandatory but crowd-thronged Pak Ou caves, where 4000 Buddha statues overlook the river.

Despite being dammed, and then double damned by the dynamiting of reefs, the Mekong muse never fails. For hours we can sit gazing from the decks, thoughts lost somewhere between the river’s silhouette ridges and spiral eddies, or watch an orb sun rise or gibbous moon fall.

“I’ve got a signal!” calls someone. We rush to our iThings. On a remote reach where probably no habitation has stood for millennia, suddenly we’re reeling in emails, uploading stuff and being tube-fed news of the appalling world beyond … and just as suddenly the signal is lost, perhaps mercifully so.

The first European to see the Mekong was Portuguese explorer Antonio de Faria in 1540. Over the centuries it has worn names reflecting various mythologies as well as its cantankerous geography — Mother of All Waters, Nine Dragons River, River of Rocks, River of Bends, Million Elephant River and, fancifully, Danube of the Orient. These days there are so many backpackers at the northern Lao town of Pak Beng that our guides suggest we just plough on.

Next day Thailand appears on the western bank, marked by, of all things, a miniature Dutch windmill. On the opposite Lao shore, thousands of hectares have been cleared for banana plantations for export to China. We are approaching the Chinese Special Economic Zone, a vast concession area in Laos where the dominant “economic activity” is a casino complex for FIFO gamblers.

There are no more villages now. The Thai shores have been tamed with stern stone levees and growing towns stretch along both shores. We land at the border port of Ban Houay Xai not for the casino but for immigration, to be stamped out of Laos.

Then, across the river at Chiang Khong, Thailand, it’s time to farewell our fragrantly good ship, so named for the champa or frangipani, national flower of Laos, and step ashore in the once-notorious Golden Triangle.

John Borthwick was a guest of Pandaw River Expeditions and the Tourist Authority of Thailand.

CHECKLIST

Champa Pandaw and sister ship Laos Pandaw cruise between Vientiane, Laos, and Chiang Khong, northern Thailand, with optional extension to Jinghong, China.

The season is from September to April.

More: pandaw.com.

THE GOLDEN TRIANGLE GLEAMS

The old opium warlords and Kuomintang smugglers are gone. The junction on the Mekong River where Myanmar, Laos and northern Thailand meet is known as the Golden Triangle and 20 years ago it had a hell of a reputation to live down. Today, on the Thai side at least, cabbages have replaced poppies, navigation and tourism are the legitimate money earners, and a huge golden Buddha oversees the whole show. The impressive Hall of Opium museum recalls the area’s rambunctious past. This Mekong shore, from “the Triangle” at Sop Ruak down through the towns of Chiang Khong and Chiang Sean, is one of the most rewarding regions of Thailand for visitors seeking an alternative to sunburn, mega-groups and bucket boozers.

Here is Thailand at home to its self. To reach it, fly from Bangkok to Chiang Rai. Check out the town’s extraordinary “White Temple”, the crystalline, Disney-like Wat Rong Khun, and then drive east to the Mekong. Among the best accommodation on the river is the Anantara Golden Triangle Resort (goldentriangle.anantara.com), whose acclaimed Elephant Camp sets the standard for visitor interactions with elephants and, further south near Chiang Saen, the serene, absolute Mekong-front chalets of Rai Saeng Arun resort.